Abstract: In the immediate aftermath of the Wagner Group’s mutiny, many commentators and analysts expected that the Kremlin’s premier private military franchise had made itself obsolete. Such thinking only accelerated following the apparent assassination of Yevgeny Prigozhin. Yet, despite relegation from the Ukrainian frontlines, exile to Belarus, and the assassination of core Wagner figures, the mercenary outfit’s operations live on, for now. Whether the group’s European wing is warehoused in Belarus indefinitely, liquidated altogether, supplanted by a Kremlin-crafted PMC, or commandeered by Moscow and the Ministry of Defense, Wagner personnel in Africa appear poised to carry on their original missions given the importance of the continent to Russia’s broader strategic ambitions. Though the mercenary mutiny and Prigozhin’s death may lead clients to raise questions about what a continued partnership with Wagner means for relations with the Kremlin, Moscow has signaled a tolerance, if not need, for Wagner or a Wagner-like entity in Africa. Abandoning Wagner clients would severely undermine Russia’s influence on the continent.

On June 23, 2023, Yevgeny Prigozhin, Wagner’s chief warlord, released a pivotal diatribe against Russia’s military leadership. A scathing Prigozhin accused the Russian army of bombing a Wagner Group camp in eastern Ukraine that had resulted in many Wagner casualties.1 While the circumstances of the event are unclear, it became a catalyst for action.2 Coupled with a looming requirement for non-Ministry of Defense (MoD) personnel to sign contracts with the Russian military, Prigozhin demanded justice, and to everyone’s surprise, he launched a mutiny targeting Sergei Shoigu and Valery Gerasimov, Russia’s Minister of Defense and Chief of Staff, respectively.3 Wagner forces eventually aborted the mutiny, but not before taking over the Southern Military District headquarters in Rostov-on-Don and halting less than 200 miles from Moscow.4

Just as shocking as the mutiny itself was the seemingly lack of consequences for the plotters. Immediately following Prigozhin’s acquiescence, many assumed that he, along with Wagner, had signed their death warrants. Yet, for nearly two months, Wagner’s operations abroad appeared unaffected, and Prigozhin continued to travel in and out of Russia without consequence. That all changed when his private jet crashed under suspicious circumstances on August 23, 2023, exactly two months after his aborted mutiny.5 Several prominent members of the Wagner Group were also onboard, including Dmitri Utkin, the group’s founder; and Valery Chekalov, Prigozhin’s deputy, head of Wagner’s operations in Syria, and key logistician for Wagner’s operations in Africa.6 While the Kremlin denied any involvement in Prigozhin’s death, hollowing out Wagner’s leadership core aligns with Moscow’s broader efforts to reassert control over the mercenary firm’s influence overseas.7

Many questions remain surrounding the fallout both from the Wagner mutiny and Prigozhin’s death. Chief among them is what this all means for Wagner’s overseas deployments, particularly in Africa.8 Banished from the frontlines of Ukraine and exiled to Belarus, the organization’s long-term durability remains very much in question and such speculation on the group’s viability post-Prigozhin is ripe.9

On the surface, Wagner’s African deployments appeared to have suffered little from Prigozhin’s self-described meltdown.10 Quite the contrary, and despite a chorus of initial reports that questioned Wagner’s viability on the continent in the aftermath of the revolt, Wagner’s operations looked to be running as business as usual. The group’s move to Belarus seemed to give Wagner new life, reinforcing its durability. Wagner’s core leadership used the Belarussian exile to their advantage, signaling their intent to recalibrate and expand their network, especially in Africa. Nowhere was this clearer than with Prigozhin’s praise of Niger’s coup leaders and his attempts to court the Sahel’s newest military junta.11

All this is to say that in the weeks leading up to the infamous plane crash, Prigozhin and Wagner’s commitment to Africa was abundantly clear. Prigozhin’s first significant post-mutiny video depicted him in the Sahel where he vowed to make Russia greater across all continents and to make Africa even freer.12 Such messaging seemed to illustrate Wagner’s acceptance of its demotion and Prigozhin’s willingness to reconstitute his focus on Africa. However, and as elucidated by investigative journalists, Prigozhin’s efforts to shore up relationships with African clients, including meeting with African delegates such as Freddy Mapouka, chief of protocol for President Toudera of the Central African Republic, during the Russia-Africa summit in St. Petersburg in late July 2023, and his short-lived propaganda campaign were less about repairing relations with Moscow and more about ensuring the economic viability of his enterprise.13 Yet, trips to Bangui and Bamako in mid-August, where Prigozhin boasted about surviving the rebellion unscathed, proved to be part of his “farewell tour.”14

While Prigozhin sought to rekindle relationships and spark new ones, the Kremlin was reportedly operating a parallel campaign designed to undercut Wagner’s partnerships with regimes in Africa and the Middle East.15 From Syria to Libya to the Central African Republic (CAR) to Mali, the Russian MoD set in motion a concerted effort to draw clients away from Wagner’s orbit and back to Moscow, promising more formal state-state engagement.16 The jostling for influence and behind-the-scenes competition exemplify just how fractured and irreparable the Prigozhin-Kremlin relationship had become in the post-mutiny environment. At the same time, jockeying to maintain relationships with Wagner clients while ditching Wagner accentuates the importance of Africa to Russia and demonstrates why Moscow cannot abandon the Wagner infrastructure entirely.

This article provides an overall assessment of what Prigozhin’s mutiny and subsequent death mean for Wagner’s operations in Africa, using open-source information and interviews with analysts closely tracking the group. The article first provides background on Wagner’s operations across its various African deployments. Second, the authors explore the post-mutiny and post-Prigozhin environments in Africa, focusing specifically on Wagner operations in the CAR and Mali. Here, the authors discuss how the Kremlin and Prigozhin appeared to be competing to shore up relations with African partners in the immediate period after the mutiny and how Prigozhin’s death does not spell the end for Wagner operations in Africa. Third, the article considers Wagner’s future on the continent. The authors assess that while Wagner’s autonomy is over and its future uncertain, it is likely that Moscow will continue to use PMCs as a foreign policy tool in Africa given the success of the Wagner model in Africa. Fourth, the authors discuss the U.S. response to Wagner and emphasize the importance of remaining proactive in countering Wagner. The article concludes with an assessment of the way forward for Wagner, noting that regardless of Wagner’s long-term future, Moscow is likely to retain the Wagner model in Africa.

Background on Wagner Operations in Africa

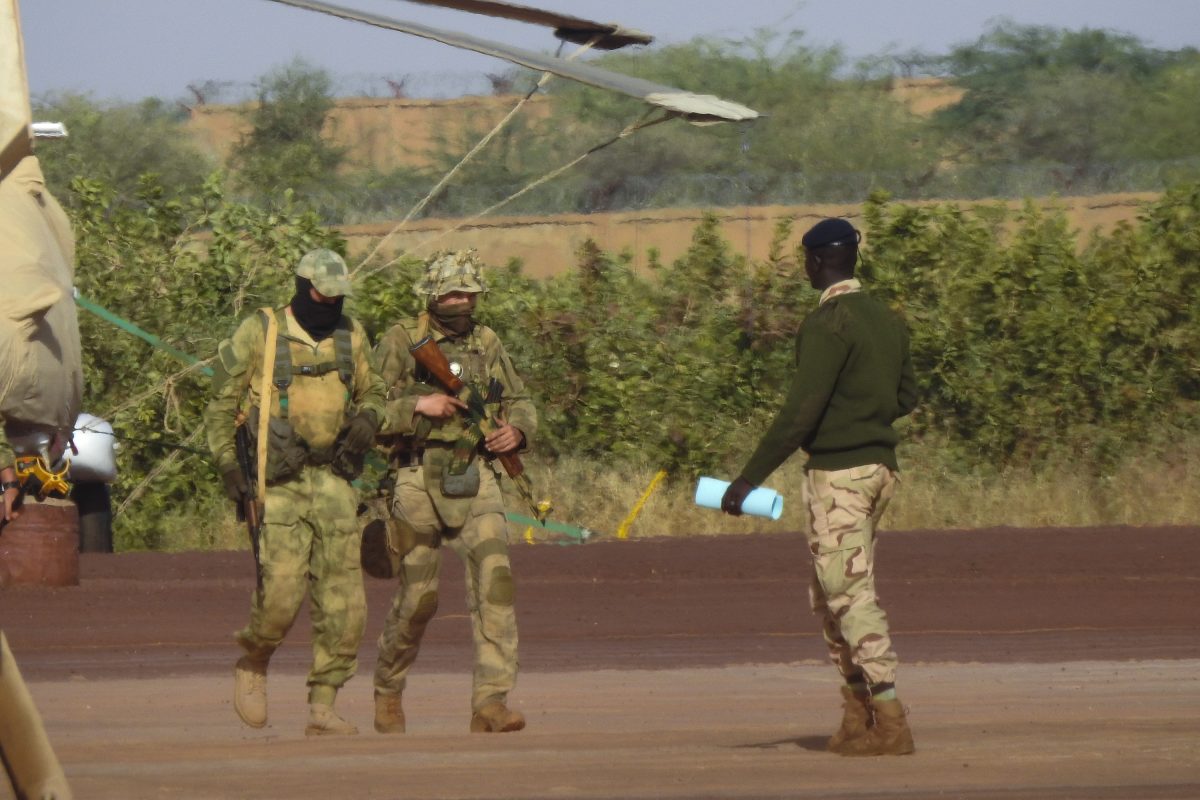

While the Wagner Group derived significant notoriety from its Ukrainian operations, the group made its mark as a Kremlin foreign policy tool and as a credible military and security outfit in Africa.17 From its deployments alongside Russian special forces in Libya to its standalone operations in Mali, Wagner has yielded significant influence for the Kremlin in at least four African countries.18 Far from Putin’s gaze, the group’s operations gradually became more autonomous. Wagner relied heavily, for instance, on Moscow for logistics and leveraged its connection to the Kremlin to attract buyers, but Prigozhin increasingly sought ways to use his vast corporate network to cut out the Russian state where possible. Prigozhin, for instance, contracted United Arab Emirates (UAE)-based firm Kratol Aviation to transport contractors and material across its African deployments in lieu of MoD aircraft, and used companies like Industrial Resources General Trading, ostensibly a Wagner shell company, to move resources such as gold to global markets.19

Commentators are eager to paint Wagner’s motivations as part of a coherent strategy, but Wagner’s contracts are as much a product of opportunism as planning. In Libya, Wagner’s involvement began as a force multiplier for the Russian military. The group’s initial operations aligned with the Russian military’s efforts to oust the Western-backed Government of National Accord in Tripoli. Libya’s vast oil wealth undoubtedly served as a clear motivator for Wagner, but its operations were more aligned with Russia’s foreign policy objectives in the region and directed by the Russian MoD. Wagner’s operations shifted to running airfields that served to facilitate transportation of personnel and equipment to their operations in other African countries such as CAR and Mali.20

Like Libya, other major Wagner deployments started under the guise of Russian security assistance but grew into something more independent, particularly at the operational level. Wagner’s initial deployment to CAR began through political jockeying by Moscow at the United Nations to secure an exemption on CAR’s arms embargo and provide trainers in late 2017.21 Wagner’s security role in CAR expanded dramatically alongside its economic interests in the country’s timber, gold, and diamond industries. Wagner parlayed these activities into a broader effort aimed at embedding itself into the local economy.22 In Mali, the Wagner Group entered alongside a deal for Russian Mi-141 attack helicopters, but the group appeared to quickly mount independent patrols while frequently killing civilians at alarming rates.23 The firm successfully exploited anti-French sentiment and capitalized on a deteriorating security situation in the region to gain favor with the ruling junta.24

Wagner’s aggressive campaign to court clients is only half the equation in understanding its expansion on the continent. African regimes facing security crises and with few viable alternatives saw Prigozhin as a counterbalance to Western and African institutions. As one analyst recently put it, Russia, and Wagner specifically, served as an effective “ally of last resort.”25 Moreover, Wagner offered democracy-skeptical leaders a chance to insulate themselves from both internal and external pressures, whether they be rebel and terrorist groups or calls for democratic reform. Even if Wagner never delivered on defeating rebels and terrorists, regime security and insulation were often sufficient enough attractions to get contracts signed.

How Wagner’s Mutiny and Prigozhin’s Death Impact Wagner Operations in Africa Overall

In the days following the Prigozhin-led mutiny, the Kremlin quickly sought to reassure Wagner’s clients in Africa. Russia’s foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, made a statement to “partners and friends” across the continent that events in Moscow would have no impact on Russia’s relationships or with the Wagner Group’s activities in Africa.26 It appears Lavrov’s comments were genuine, to a degree. In the days and weeks following the mutiny, Wagner’s operations on the continent remained largely unaffected. Rumors that Wagner forces were evacuating CAR, for example, proved to be erroneous.27 Moreover, open-source flight tracking identified that a Russian Ministry for Emergency Situations aircraft, an aircraft used to transport Wagner personnel in the past, continued to fly similar routes from Moscow to Damascus to Bamako and back.28 In short, just days before Prigozhin’s death, Wagner personnel, and perhaps Prigozhin himself, appeared to still be benefiting from Russian logistical support in Africa.

Yet, Prigozhin’s death has ushered in renewed debate about the likelihood of Wagner’s sustained operations across Africa and Middle East. At this point, it may be too early to assess with sufficient confidence what Wagner’s future holds, if anything, and what a post-Prigozhin Wagner entails. However, Moscow is unlikely to abandon the Wagner model in its entirety because it serves Kremlin interests to build influence in Africa and to threaten or damage Western influence in exchange. Equally important is that fully dismantling the Wagner enterprise would be self-defeating as the Wagner Group set the foundation, developed the infrastructure, and facilitated the political, economic, and social connections that have enhanced Moscow’s reach.

At the time of publication, Putin’s Wagner dilemma post-Prigozhin is still in its infancy, but it is clear that the Russian president is making every effort to counter any potential Wagner backlash while accelerating efforts to exert control over it. Such efforts were already well underway as Prigozhin’s mutiny unfolded in late June, with reports suggesting that Wagner personnel in Syria were being rounded up and forced to sign contracts with the Russian MoD or leave the country.29 Then, just two days after Prigozhin’s plane went down, Putin signed a decree requiring all paramilitary units, like mercenaries, to swear an oath of allegiance to the Russian state.30 In addition, Prigozhin’s funeral was kept secret, an intentional effort by the Kremlin to avoid any fanfare.31

While the death of Prigozhin is undoubtedly a blow to Wagner, assuming the group is incapable of operating in his absence is misguided. Prigozhin’s skills as a propagandist, his business acumen and capacity to thrive in corruption, and his success in sanctions evasion provided Wagner with a comparative advantage. But Prigozhin was far from a military operator, and despite his death, many of Wagner’s key personnel in Africa appear to be “staying put for now.”32 In CAR, for instance, Vitali Perfilev and Dimitri Sytyi, two key Wagner leaders, are still running operations.33 The main challenge for Wagner is that its destiny is not its own. Defense Minister Shoigu is expected to have a key role in deciding Wagner’s fate, and the Russian MoD appears committed to ensuring that Wagner’s days of autonomy are over.34 But while Moscow will want substantial oversight, in the short term, Wagner’s African operations—even if Wagner is not at the helm—are likely to march on.

The Impact in the Central African Republic

CAR is host to Wagner’s most comprehensive operations. As a result, even with Prigozhin’s death, it is unlikely that the mercenary firm and its network of business entities will exit CAR any time soon.35 The group’s economic portfolio in CAR is particularly diversified, ranging from investments across traditional economic activities like gold and diamond extraction to more atypical ventures into the forestry industry, and alcohol and coffee production.36 Wagner’s economic base and connections to the central government make it difficult, if not impractical, for the Russian state to seamlessly take over the broad portfolio of Wagner-adjacent activities. Some analysts have speculated that if the Kremlin was complicit in the death of Prigozhin, the delay in action may have stemmed from a need to assess and audit Wagner operations in CAR in order to better understand its network in efforts to usurp control over it.37 Tying up loose ends was vital before burying Prigozhin once and for all.38

In addition to Wagner’s economic web, the mercenary firm’s deep involvement with the Touadera government over the past five years discounts the possibility of a withdrawal of Russian support. CAR officials met with both Putin and Prigozhin after the mutiny to keep communication lines open.39 After proclaiming themselves the saviors of CAR, leaving would almost certainly lead to a political and military crisis and a massive hit to Russia’s image as a provider of regime security on the continent. In fact, Wagner’s value as a pseudo-diplomatic tool in CAR all but ensures the Kremlin will retain a mercenary-like outfit in Bangui if not elsewhere.40

Nowhere is the deleterious nature of Wagner more apparent than in CAR’s recent constitutional referendum.41 The proposed changes in the referendum were controversial enough that the president needed to extrajudicially remove several judges to even hold it. A “yes” vote meant supporting increased presidential term limits, an increase of term length to seven years. It also restricted who could run for president, and gave the presidency more power over the judiciary.42 Such tactics are not unfamiliar on the continent.43 Wagner’s infiltration of CAR’s political and economic spaces sets the foundation for its influence and impact on the regime’s trajectory, even if CAR has not had as violent a break from France and the United Nations as Mali has.44

Much of the movement of Wagner forces in CAR immediately after Prigozhin aborted the mutiny in Russia, a troop rotation that many suspected was a sign of Wagner’s departure, had more to do with ensuring the referendum ran smoothly; and it did. Initial estimates alleged that 95 percent of votes cast were in support of the new constitution, despite disguised opposition boycotts and limited access in rural areas, which neither Wagner nor Central African authorities worked to address.45 The last big vote in CAR, the 2020 elections, had resulted in a rebel offensive that nearly dislodged Touadera’s regime. With Wagner, co-opted rebel groups, and bilateral Rwandan forces in play, that was not going to happen again.46

Before the vote, there was speculation that France and the United States were contemplating a deal with Touadera that if he expelled Russia’s mercenaries, they would drop opposition to Touadera’s third term.47 Such bargaining is reminiscent of a Cold War era approach that falsely puts democratic value and geopolitical goals in conflict.

Wagner’s economic position in CAR makes it more resilient to dismantlement than several of its other enterprises and deployments.48 Putin would loath giving up these resources, particularly while his regime is sanctioned and precious metals are limited in supply. Wagner-affiliated shell companies, including Meroe Gold, Lobaye Invest, and Diamville, offer multiple illicit economic channels, likely through the UAE, that provide gold and possibly diamonds to Russia.49 Abandoning these projects altogether would be unwise, but Russian officials will likely find it difficult to keep so many plates spinning after Prigozhin’s death.

At the same time, with Prigozhin out of the picture, the Kremlin has an opportunity to commandeer these economic outfits, rebrand them, and even install new ownership structures. Putin’s regime has a history of commandeering businesses of oligarchs through manipulation of Russia’s legal system—as seen in its hostile takeover of Michael Khorovsky’s Yukos Oil.50 Appeasing Wagner personnel will be incumbent in the short-term, and while some percentage of Wagnerites may be disgruntled over the Kremlin’s efforts to reassert control over them and could choose to leave, their loyalty is more likely to a paycheck than to a dead Prigozhin.

The Impact in Mali

Comparatively, Wagner operations in Mali have been more challenging. Deterred by Western, particularly Canadian, mining companies and local interests, Wagner has been unable to secure the types of lucrative resource extraction deals that its leadership appears to prefer in lieu of direct payment, and its operations have been funded by the Malian state instead.51 Wagner’s limited economic portfolio in Mali means that the Russian government may find it easier to overtake Wagner’s portfolio in Mali without needing to unravel complicated Wagner economic operations, as it would likely need to do in CAR.

Even before Prigozhin’s death, questions loomed surrounding the strength of Wagner’s relations with the junta. Malian junta leader Assimi Goïta voiced support for Putin at the Russia-Africa Summit just days after the Prigozhin mutiny and allegedly spoke with Putin directly.52 And, despite Prigozhin’s death, Russia’s deputy ambassador to the United Nations confirmed that Russia would continue providing Mali with “comprehensive support”—what many assume is a clear signal that Moscow is unlikely to abandon Wagner forces in Bamako.53

The Kremlin needs Wagner, or something akin to it, to hold down the fort, literally and diplomatically. A Wagner withdrawal without a clear operational plan to replace it would only accelerate the pace at which terrorist organizations gain control over territory in the country. In a report that was distributed in the summer of 2023, U.N. experts noted that the Islamic State Greater Sahara (ISGS) “almost doubled its areas of control in Mali” in less than a year.54 Meanwhile, al-Qa`ida affiliate JNIM has exploited the ISGS territory grab, situating itself as “the sole actor capable of protecting populations against Islamic State in the Greater Sahara.”55 The oncoming MINUSMA withdrawal,a not to mention France’s withdrawal of Operation Barkhane, has only heightened the security challenges. Reports of a potential temporary truce between ISGS and JNIM until after the U.N. withdrawal only add to concerns of a growing terrorist threat.56 For its part, Wagner has done little to rectify security challenges in the country and has instead been complicit in exacerbating insecurity.57 At the same time, and prior to Prigozhin’s death, analysts observed ongoing base construction at Wagner’s headquarters in Bamako.58 Such base expansion was interpreted as a signal of Wagner’s intention on fortifying its position in Mali. But with the Kremlin’s diplomatic onslaught to lure Wagner clients away from Wagner, the effort may have been more indicative of Wagner attempting to compete in the face of Moscow’s efforts to reclaim control over it.59 Either way, Russia is unlikely to abandon Bamako given the geopolitical and reputational costs it would face in doing so.

Such reasoning is reinforced by Moscow’s concerted effort to reassure Mali’s junta that it is a committed partner. On August 30, 2023, Russia vetoed a U.N. Security Council resolution that would have extended sanctions against Mali.60 Additionally, and despite claims that Wagner personnel were leaving Mali following Prigozhin’s death, personnel movements out of Mali appear to be more about troop rotations than a mass exodus of Wagner employees, echoing personnel rotations in CAR after the Prigozhin mutiny.61 Though difficult to confirm, some evidence even points to the movement of Wagner personnel from Syria to Mali, both to bring in more experienced operators as well as personnel that are either more loyal to the Kremlin and/or under the MoD’s direct control.62

Regardless of the way forward, Wagner and the Russian state are in for a challenge in Mali. On September 8, 2023, JNIM claimed it shot down a helicopter belonging to Wagner.63 ISGS and AQIM propaganda already casts Russian mercenaries as the new enemy in their recruiting drives and public statements.64 Such anti-Russian propaganda should worry a Russian regime with a history of violence in Chechnya and the Caucasus, particularly when Russian deployments have already threatened these groups. Putin will need to decide whether such a deployment under the direct supervision of the Russian military is worth the potential geopolitical blowback.

Wagner’s Malian experiment and its uncertain future is indicative of the dangers and difficulties faced by regimes hellbent on contracting mercenary outfits. Regardless of Mali’s strained relations with Paris and the United Nations, betting on Wagner has painted the junta into a precarious corner.65 It is unreasonable to expect that Wagner’s contingent of 1,000 personnel in Mali can adequately supplant the nearly 13,000-strong MINUSMA force.66 Moscow’s efforts to stress its commitment to Mali have been notably unspecific, but it has kept up the propaganda campaign with its deputy ambassador to the United Nations recently stating that Mali’s decision to count on Russia is “keeping our former Western partners up at night.”67 b For Moscow, relying on the Wagner footprint there is the most pragmatic approach in the short term.

Wagner’s Future Operations on the Continent

The longer-term future of Wagner in Africa remains anyone’s guess. As noted, Wagner’s post-mutiny period seemed to reflect a conscious effort to reconstitute its mission set and focus on expeditionary activities and overseas deployments far from the frontlines of Ukraine. On July 19, 2023, Prigozhin and a figure believed to be Dmitri Utkin, promised that Wagner’s relegation to Belarus did not signal its end, rather it was “just the beginning.”68 And, as mentioned earlier, Prigozhin made a concerted effort to assure African partners that the Wagner saga was in fact under control, courting African delegates at the Russia-Africa summit just one month after the mutiny.69

That all appeared to be window-dressing. Prigozhin’s efforts to move on from the mutiny are now a moot point. The Kremlin appears intent on ensuring that Wagner or whatever vanguard it taps to take over the Africa mission understands its place in the Russian hierarchy. Ambiguity notwithstanding, Wagner personnel will undoubtedly experience heartburn over being subservient to the Russian MoD or being folded into another mercenary outfit, but they will have little say in the matter. What they are likely to have, however, is continued work as Russia is poised to take the mantle from Wagner and push forward with its African missions one way or the other. Reinforcing this point, a Russian delegation headed by Deputy Defence Minister Yunus-Bek Yevkurov undertook an African tour in the days before and immediately after Prigozhin’s death, meeting first with General Khalifa Haftar, leader of the Wagner-backed Libyan National Army in Libya, then reportedly visiting Bamako, meeting with Burkina Faso’s junta in Ouagadougou, before heading to Bangui.70

Where Wagner or its replacement might venture next is a complicated question. Before Prigozhin’s death, Wagner was floated as a potential option for Niger’s junta, which, at the time, was dealing with a looming ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States) intervention. Reeling from the uncertainty and in the face of Western condemnation, Nigerien General Salifou Modi, vice president of the junta, flew to Bamako to meet with Wagner officials.71 But both ECOWAS’ threats and Wagner’s promises of assistance have proven to be empty.72 For Wagner, the ability to shift assets from other African deployments to Niger was questionable even before Prigozhin’s death, given commitments in Ukraine and limited Russian transport support. However, based on Wagner’s historic track record of capitalizing on insecurity and civil-military crises, Moscow will look to deploy Wagner or its successor organization wherever the opportunity arises. This time, however, Russia will make sure the leash is much shorter.

Walking the Walk: What Can the United States Do?

Regardless of Wagner’s long-term future, it is important to understand that the Kremlin’s mercenary diplomacy is here to stay. Wagner may have spiraled out of the Kremlin’s control and been given too much autonomy, but the value of paramilitary and mercenary groups as a foreign policy tool is not lost on Moscow. Meanwhile, the U.S. government has reached a critical inflection point in its Africa policy. Even if the deaths of Prigozhin and Utkin stagnate Russia’s momentum in Africa, the coups in Niger and Gabon raise serious strategic dilemmas. Niamey remains one of, if not the only, remaining bastion of American-led counterterrorism activity in the Sahel. A U.S. drone base73 and a modest military assistance program74 there demonstrated that African leaders need not contract entities like Wagner to counter militant threats—though such efforts clearly did little to address underlying domestic political volatility that enabled the coup.75 Today, U.S. officials must walk a tightrope between what can seem to be opposing interests: either supporting hard-nosed strategic and military interests or supporting democratic processes and opposing non-democratic transitions, while recognizing this can be a false dichotomy when it comes to long-term American ideals and interests. The Biden administration’s reluctance to brand Chad’s transition as unconstitutional following the death of Idris Déby in 2021, for instance, has not gone unnoticed, putting the United States in a difficult position when other undemocratic transitions take place.76

As a result, when it comes to Niger, U.S. government officials both advocate for a return to democratic governance and emphasize the importance of U.S. partnership with Niger’s armed forces.77 The unresolved tension between promoting values of democratic integrity and maintaining operations also knocks the United States out of alignment with France, a key ally and NATO partner, as well as ECOWAS states Senegal, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Nigeria that are far more assertive on the issue of restoring the president to power.78 Although U.S. operations in the Sahel will likely continue, Niger’s role in a U.S.-backed counterterrorism mission remains an open question, even with the United States resuming drone and manned intelligence and surveillance operations after reaching an agreement with the junta.79 That question became even more complicated when Niger, along with Mali and Burkina Faso, signed a mutual defense pact, the Alliance of Sahel States, on September 16, 2023.80

The fundamental challenge is that the United States has no clear strategy in cases when democratic values do not align with African politics, or rather, when a small contingent of political and/or military elite decide that their democratic experiment has run its course. Accusations from within the American body politic that the U.S. training of African militaries or U.S. military aid to specific African nations caused instability are symptomatic of strategic uncertainty.81 While some will view this as an opportunity to withdraw U.S. security support across the continent, doing so without a revitalized approach would add fuel to the fire of jihadism and democratic backsliding. It would simultaneously embolden Moscow as it tries to piece together its post-Wagner puzzle in Africa.

On the other hand, Africa’s insurgencies have made it clear that limited support is not enough. In particular, instability in the Sahel and West Africa is growing, but U.S. resources to help are not. Today, sub-Saharan Africa is a marginal part of U.S. foreign policy, particularly after U.S. failures in Somalia in the early 1990s.82 Despite its importance as a base for terror activity during al-Qa`ida’s formative years, including the bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998,83 sub-Saharan Africa was a secondary concern in the U.S. “war on terror” after 9/11 while the Middle East and North Africa were prioritized. That so much of the discussion of Sahelian security focuses on Wagner reflects U.S. anxieties over great power competition, rather than African security in and of itself. Nonetheless, U.S. officials in Africa have access to hundreds of millions of dollars, so making the most of that funding is key to operationalizing the Biden administration’s strategies to counter extremism in Africa.84

On the Wagner front, and despite the fracturing between Prigozhin and the Russian MoD, the United States has at least rhetorically signaled that it is still taking the mercenary group seriously. The U.S. representative to the United Nations, Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield, confirmed as much roughly a month after Prigozhin’s mutiny when she stated “that any attacks by the Wagner Group will be seen as an attack by the Russian Government.”85 Remarks such as these are important in that they counter any attempt the Kremlin may make to reinstitute the veil of plausible deniability in its sponsorship of mercenary proxies.86 Yet, remarks alone are insufficient for countering Wagner in Africa, let alone Moscow’s broader weaponization of private military companies (PMCs). And while a Pentagon spokesperson in responding to a journalist’s question recently claimed that Wagner is “essentially over,” complacency in countering Wagner, even if it is weakened, sets a dangerous precedent.87 A proactive approach is imperative, one that anticipates ways in which the Kremlin will seek to alter Wagner’s surface features—its name and public figures—rather than its functionality, as a method to skirt sanctions and find new clients.

Conclusion

The Sahel’s security challenges are bigger than Russia. Even if Prigozhin’s death stunts Russian PMCs or formal expansion in the Sahel, the wave of external threats and internal instability Wagner helped facilitate will continue to challenge African, European, and American policymakers. Washington’s willingness to release statements in support of democracy and security in Africa needs to be matched with a serious effort to build consensus around the imperative to stop the spread of jihadism now and strengthen the stability of the region’s democratic governments. Wagner may be floundering, but terrorist threats are not, and neither will Moscow’s efforts to capitalize on persistent insecurity and civil-military volatility.

Unfortunately, potential U.S. partners in Africa and Europe seem far from a consensus about the severity or a way forward. In 2022, a coalition of West African governments called the Accra Initiative agreed in theory to form a multilateral joint taskforce to help contain the spread of extremist groups but is struggling to fund it.88 France is reeling from the perception in the Sahel that its counterterrorism efforts are neo-imperialist and ineffective.89 The United Kingdom recently moved to proscribe Wagner as a terrorist organizationc but withdrew its peacekeepers from Mali after tensions between the United Nations and the Wagner-backed junta reached a boiling point.90 Lastly, Germany and the European Union are seeking to consolidate their security assistance missions in coastal West Africa, in the hopes of preventing more democracies from falling to their own militaries.91

Russia benefits from the international community’s lack of consensus. Even if its mercenaries and arms sales cannot solve the wider crises of state failure, extremism, and ecological disaster, Moscow will be able to package its assistance as the hard but necessary measures that appeal to coup leaders in the short term.

Returning to the question of Wagner specifically, what belies the mercenary outfit and its operations in Africa is ambiguous. Prigozhin’s mutiny and death have put the Kremlin into triage mode as it works to untangle the Wagner network and assess the best path forward. There are at least three options the Russian state may consider: abandon the organization completely, commandeer the organization entirely and house it under Russia’s defense and intelligence infrastructure, or attempt a public-private partnership.92 None of these are particularly good options, but some are better and/or more likely than others.

First, abandoning the Wagner Group entirely, the most unlikely scenario, would exacerbate already volatile security situations across Wagner’s operations in CAR, Mali, Libya, and elsewhere, as Wagner units would likely either withdraw or form their own fiefdoms, allowing terrorist groups and insurgents to roam free. This scenario would also be the most damaging for Moscow’s international reputation, and losing friends in the midst of the ongoing war in Ukraine is an undesirable outcome. Option two, a complete Russian state takeover, would require the diversion of resources and assets currently dedicated to the war in Ukraine. As Russian experts note, the administrative burden, particularly for a Russian military that is focused on operations in Ukraine, would also be substantial if not impractical.93 Moreover, identifying which Russian institutions, whether the MoD or the Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU), would be the right fit for inheriting Wagner is also up for debate.94 Moreover, folding Wagner formally into state institutions removes any remaining facade of plausible deniability and increases Moscow’s accountability over its forces. A third option, the public-private partnership, while perhaps the most prudent involves elevating a new individual to Prigozhin’s position, potentially causing instability in Putin’s inner circle.95 While Prigozhin is far from irreplaceable, he was effective in managing a complex web of business entities across multiple countries and amidst mounting international pressure.96 Few oligarchs in the Russian sphere of influence are presumed to have the ability to maintain Prigozhin’s business contacts or replicate his networks as effectively as he did.97

Regardless of what approach is taken, Prigozhin’s model of economic exploitation, disinformation, and military assistance is here to stay.98 This model has proved useful in Russia’s campaign for international influence, helping Russia seize control of the military assistance program in Mali and dispelling anti-Western and pro-Russian propaganda across Africa. It has provided the added benefit of aiding Russia via sanctions evasions through gold, diamond, and forestry concessions exchanged for military assistance in places such as CAR and Sudan. There is also a pragmatic element that makes maintaining a Wagner-like entity attractive. “If the Kremlin wants to reduce Wagner’s influence on the doorstep of Moscow, it would be logical to send more mercenaries to Africa.”99 Ensuring mercenaries are far from centers of political power has been the historical norm. For Putin, keeping mercenaries—some who may harbor resentment at the death of Prigozhin—busy abroad both sends a signal of commitment to partners in Africa and keeps Wagner loyalists at bay while Moscow determines Wagner’s long-term fate.

Overall, the Wagner Group has proven too valuable both economically and politically to abandon, but also too complex to effectively commandeer entirely. Wagner has played a crucial role in galvanizing support for Russia on the African continent and has enabled the Kremlin to compete for influence at a relatively low cost in comparison to strategic competitors. Irrespective of the long-term future of Moscow’s most infamous mercenary outfit, the Wagner model, especially in Africa, is likely to remain a persistent and enduring threat in the years ahead. CTC

Dr. Christopher M. Faulkner is an Assistant Professor of National Security Affairs in the College of Distance Education at the U.S. Naval War College. His research focuses on militant recruitment, private military companies, and national/international security. The views expressed are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Naval War College, Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. X: @C_Faulkner_UCF

Raphael Parens is a Eurasia Fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. He studies African conflict, Russian military policy, and paramilitary groups. The views expressed are the author’s own. X: @moresecurityint

Marcel Plichta is a Ph.D. Candidate at the University of St Andrews and a fellow at the Centre for Global Law and Governance. His research focuses on the use of force by small states. X: @Plichta_Marcel

© 2023 Christopher Faulkner, Raphael Parens, Marcel Plichta

Substantive Notes

[a] While MINUSMA was terminated on June 30, 2023, the official and complete withdrawal of MINUSMA troops is expected on December 31, 2023. See “Security Council ends MINUSMA mandate, adopts withdrawal resolution,” United Nations, June 30, 2023.

[b] Recall that this is the same deputy ambassador who claimed back in February 2022 that Russia had no intention of invading Ukraine. See “Russia has ‘no intention’ to invade Ukraine, deputy U.N. ambassador says,” CBS, February 16, 2022.

[c] The U.K. Home Office issued the draft to proscribe Wagner a terrorist organization on September 6, 2023. Following parliamentary debate, the proscription became official on September 15, 2023. “Russian Wagner Group Declared Terrorists,” UK Government, September 6, 2023; “Wagner Group Proscribed,” UK Government, September 15, 2023.

Citations

[1] Oleksiy Sorokin, “Prigozhin Accuses Russian Army of Attacking Wagner, Threatens to Respond,” Kyiv Independent, June 23, 2023.

[2] Aric Toler, “Site of Alleged Wagner Camp Attack Recently Visited by War Blogger,” Bellingcat, June 23, 2023.

[3] Joshua Yaffa, “Inside the Wagner Group’s Armed Uprising,” New Yorker, July 31, 2023.

[4] Mariano Zafra and Jon McClure, “36 Hours and Hundreds of Kilometers of the Mercenary Mutiny in Russia,” Reuters, June 26, 2023.

[5] Jesse Yeung and Lauren Said-Moorehouse, “What Could Have Caused the Plane Crash that Reportedly Killed Wagner Warlord Yevgeny Prigozhin?” CNN, August 25, 2023.

[6] Sean Seddon, “Who is Dmitry Utkin and Who Else Was on the Plane?” BBC, August 24, 2023; Samuel Bendett, “As Russia’s Rosaviatsia reported last night, ‘Valery Chekalov was on the list of passengers along with Prigozhin and Utkin …,” X, August 24, 2023.

[7] Benoit Faucon, Drew Hinshaw, Joe Parkinson, and Nicholas Bariyo, “The Last Days of Wagner’s Prigozhin,” Wall Street Journal, August 24, 2023.

[8] Raphael Parens, “Wagner Mutiny Ex Post Facto: What’s Next in Russia and Africa?” Foreign Policy Research Institute, July 26, 2023; Nosmot Gbadamosi, “Will Wagner Stay in Africa?” Foreign Policy, June 28, 2023.

[9] Christopher Faulkner, Colin Clarke, and Raphael Parens, “Wagner Group Licks Its Wounds in Belarus,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, August 11, 2023.

[10] Tatiana Stanovaya, “Beneath the Surface, Prigozhin’s Mutiny has Changed Everything in Russia,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, July 27, 2023.

[11] Andrew Osborne, “Prigozhin Hails Niger Coup, Touts Wagner Services,” Reuters, July 29, 2023.

[12] Anton Gerashchenko, “Prigozhin published a new video,” X, August 21, 2023.

[13] Max Seddon and Andres Schipani, “Wagner Boss Prigozhin Appears on Sidelines of Russia-Africa Summit in St. Petersburg,” Financial Times, July 27, 2023.

[14] Faucon, Hinshaw, Parkinson, and Bariyo; Pjotr Sauer, “Yevgeny Prigozhin Spoke of Threats to His Life Days Before Death, Video Appears to Show,” Guardian, August 31, 2023.

[15] Faucon, Hinshaw, Parkinson, and Bariyo.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Christopher Faulkner, “Undermining Democracy and Exploiting Clients: The Wagner Group’s Nefarious Activities in Africa,” CTC Sentinel 15:6 (2022).

[18] Alec Bertina, “The Wagner Group: The World’s Most Infamous PMC,” Grey Dynamics, June 26, 2023.

[19] “Treasury Sanctions Russian Proxy Wagner Group as a Transnational Criminal Organization,” U.S. Department of Treasury, January 26, 2023; “Treasury Sanctions Illicit Gold Companies Funding Wagner Forces and Wagner Group Facilitator,” U.S. Department of Treasury, June 27, 2023.

[20] “Written Submission on Wagner’s Activities in Libya Submitted by [Organisation name redacted] (WGN0014),” UK Foreign Affairs Committee, June 23, 2022.

[21] Marcel Plichta, “Russia Is Back in Africa – And Making Some Very Odd Deals,” Defense One, May 22, 2018.

[22] “Wagner Allowed to Keep African Businesses After Mutiny,” Moscow Times, July 11, 2023.

[23] “Wagner Group Operations in Africa: Civilian Targeting Trends in the Central African Republic and Mali,” ACLED, August 30, 2022; Guy Martin, “Mali Officially Takes Delivery of Mi-171 Helicopters,” DefenceWeb, December 6, 2021.

[24] Joseph Siegle and Daniel Eizenga, “Russia’s Wagner Play Undermines the Transition in Mali,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, September 23, 2021; Wassim Nasr and Raphael Parens, “TSC Insights: France’s Missed Moments in the Sahel,” Soufan Center, July 6, 2023.

[25] Jack Margolin, “The New Russian Mercenary Marketplace,” Riddle, August 21, 2023.

[26] Clea Calcutt and Laura Kayali, “Wagner and Russia are Here to Stay in Africa, Says Kremlin’s Top Diplomat,” Politico, June 26, 2023.

[27] Judicael Yongo, “Central African Republic says Wagner Troop Movement is Rotation Not Departure,” Reuters, July 8, 2023.

[28] Fabian, “#Mali – A ‘Russia – Ministry for Emergency Situations (MChs)’ Il-76 TDP (reg. RA-76845 | 152C2D) is currently heading to #Bamako …,” X, August 19, 2023.

[29] Suleiman Al-Khalidi and Maya Gebeily, “Syria Brought Wagner Fighters to Heel as Mutiny Unfolded in Russia,” Reuters, July 7, 2023.

[30] Ece Goksedef, “Wagner Mercenaries Must Swear Allegiance to Russia – Putin,” BBC, August 26, 2023.

[31] “‘We Don’t Need Heroes Who Marched on Moscow’: Kremlin and FSB Decided to Bury Yevgeny Prigozhin Secretly, Without Military Honors,” Meduza, August 30, 2023.

[32] Author’s (Faulkner) interview, Alec Bertina, September 2023.

[33] Rachel Chason and Barbara Debout, “In Wagner’s Largest African Outpost, Russia Looks to Tighten Its Grip,” Washington Post, September 18, 2023.

[34] John Lechner and Sergey Eledinov, “Now Prigozhin is Gone, What Happens to Wagner?” Open Democracy, August 30, 2023.

[35] John Lechner and Marat Gabidullin, “Why the Wagner Group Won’t Leave Africa,” Foreign Policy, August 8, 2023.

[36] Parens, “Wagner Mutiny Ex Post Facto.”

[37] Colin Clarke, “I joined @AlJazeera to speak about the apparent death of Wagner boss …,” X, August 24, 2023.

[38] Simon Sebag-Montefiore, “What Prigozhin’s Death Reveals About Putin’s Power in Russia,” TIME, August 24, 2023.

[39] Seddon and Schipani.

[40] Lechner and Gabidullin.

[41] Natasha Booty and Yusuf Akinpelu, “Central African Republic President Touadera Wins Referendum with Wagner Help,” BBC, August 7, 2023.

[42] Miteau Butskhrikidze, “President of Central African Republic Orders Removal of Top Judge From Constitutional Court,” Jurist, October 25, 2022.

[43] Joesph Siegle and Candace Cook, “Circumvention of Term Limits Weakens Governance in Africa,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, September 14, 2020.

[44] Vienney Ingasso, John Lechner, and Marcel Plichta, “Wagner is Only One Piece of the Central African Republic’s Messy Puzzle,” World Politics Review, January 31, 2023.

[45] Booty and Akinpelu.

[46] “Rwanda’s Growing Role in the Central African Republic,” International Crisis Group, July 7, 2023.

[47] Peter Fabricius, “France and the US’s Possible Faustian Pact with CAR’s Touadera,” Institute for Security Studies, July 28, 2023.

[48] “Architects of Terror: The Wagner Group’s Blueprint for State Capture in the Central African Republic,” Sentry, June 2023.

[49] Peter Hobson, “Exclusive: From Russia with gold: UAE cashes in as sanctions bite,” Reuters, May 25, 2023.

[50] Catherine Belton, Putin’s People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and Then Took on the West (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020).

[51] Michael Shurkin, “The Malian government is reluctant to hand Wagner sweet heart mining deals …,” X, July 21, 2023.

[52] “Mali leader thanks Russia for support in fighting ‘terrorism,’” Reuters, July 28, 2023; “Putin, Mali’s leader emphasize need for peaceful settlement in Niger,” TASS (Russian News Agency), August 15, 2023.

[53] Michelle Nichols, “After Wagner Chief Death, Russia Vows to Keep Helping Mali,” Reuters, August 29, 2023.

[54] Edith M. Lederer, “UN Experts Say Islamic State Group Almost Doubled the Territory They Control in Mali in Under a Year,” Associated Press, August 26, 2023; “Final report of the Panel of Experts on Mali established pursuant to Security Council resolution 2374 (2017),” United Nations, August 3, 2023.

[55] “Final report of the Panel of Experts on Mali,” p. 17.

[56] Caleb Weiss, “Analysis: Setting the Stage for Mali’s Near Future,” FDD Long War Journal, September 11, 2023.

[57] Ladd Stewart, Heni Nsaibia, and Nichita Gurcov, “Moving Out of the Shadows. Shifts in Wagner Group Operations Around the World,” ACLED, August 2, 2023.

[58] Catrina Doxsee, Joseph Bermudez, and Jennifer Jun, “Base Expansion in Mali Indicates Growing Wagner Group Investment,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, August 15, 2023.

[59] Anton Troianovski, Declan Walsh, Eric Schmitt, Vivian Yee, and Julian E. Barnes, “After Prigozhin’s Death, a High-Stakes Scramble for His Empire,” New York Times, September 8, 2023.

[60] “Veto by Russian Federation Results in Security Council’s Failure to Renew Travel Ban, Asset Freeze against Those Obstructing Mali Peace Agreement,” United Nations, August 30, 2023.

[61] Casus Belli, “Sources says #Wagner started to leave different positions in Mali,” X, August 31, 2023.

[62] Author’s (Faulkner) interview, Wassim Nasr, September 2023.

[63] Wassim Nasr, “#Mali #JNIM #AQMI #Ségou revendique un affrontement avec #Wagner,” X, September 8, 2023.

[64] Wassim Nasr, “How the Wagner Group Is Aggravating the Jihadi Threat in the Sahel,” CTC Sentinel 15:11 (2022).

[65] Feras Kilani, “Inside Mali: What Now for the Country that Bet Its Security on Wagner?” BBC, August 25, 2023.

[66] Ibid.

[67] Nichols.

[68] Mary Ilyushina, “Prigozhin says Wagner Mercenary Group for now Will Not Fight in Ukraine,” Washington Post, July 20, 2023.

[69] “Prigozhin: Wagner Boss Spotted in Russia During Africa Summit,” BBC, July 28, 2023.

[70] “Russian Army Officials Visit Libya After Haftar Invite,” Moscow Times, August 22, 2023; All Eyes on Wagner, “Should We Say the Tour of the Russian MoD continues?” X, August 30, 2023; “Burkina Faso says leader discussed possible military cooperation with Russian delegation,” Reuters, August 31, 2023; All Eyes on Wagner, “The Tour Continues!” X, September 1, 2023.

[71] Wassim Nasr, “#Niger selon deux sources maliennes …,” X, August 2, 2023; Sam Mednick, “Niger’s Junta Asks for Help from Russian Group Wagner as it Faces Military Intervention Threat,” Associated Press, August 5, 2023; Sidonie Aurore Bonny, “Niger Junta Appoints Cabinet, Member of Military as President,” Anadolu Ajansi, August 3, 2023.

[72] Marcel Plichta, “Russia’s Mercenaries Don’t Want to Control Africa. They Want to Loot it,” Defense One, March 22, 2022.

[73] Carla Babb, “US-Constructed Air Base in Niger Begins Operations,” Voice of America, November 1, 2019.

[74] “U.S. Defense and Security in Niger: Enhancing Our Partner’s Capacity,” U.S. Embassy Niger, January 21, 2021.

[75] Jeff Schogol, “The US can’t use its $110 million drone base in Niger,” Task & Purpose, August 1, 2023; Michael Crowley, “With Aid on the Line, Biden Officials Debate ‘Coup’ Finding for Niger,” New York Times, September 6, 2023.

[76] Robbie Gramer, “Biden Defaults to ‘War on Terror Approach’ to Chad,” Foreign Policy, May 13, 2021.

[77] Hannah Rae Armstrong, “Niger’s Coup and America’s Choice,” Foreign Affairs, August 29, 2023.

[78] Katarina Hoije and Antony Sguazzin, “Niger Coup One Too Many for West African Leaders,” Bloomberg, August 4, 2023.

[79] “US Military Resumes Drone, Crewed Aircraft Operations in Post-Coup Niger,” Al Jazeera, September 14, 2023.

[80] “Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso Establish Sahel Security Alliance,” Al Jazeera, September 16, 2023.

[81] Emma Ashford and Matthew Kroenig, “Does U.S. Military Training Embolden Coup Plotters in Africa,” Foreign Policy, August 4, 2023.

[82] Philip B. Dotson, “The Successes and Failures of the Battle of Mogadishu and Its Effects on U.S. Foreign Policy,” Channels 1:1 (2016).

[83] “East African Embassy Bombings,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, n.d.

[84] “U.S. Strategy to Sub-Saharan Africa,” The White House, August 2022.

[85] “Remarks by Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield at a Virtual New York Foreign Press Center Briefing on the U.S. Presidency of the UN Security Council,” United States Mission to the United Nations, July 31, 2023.

[86] András Rácz, “Band of Brothers: The Wagner Group and the Russian State,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, September 21, 2020.

[87] “Wagner Group is Essentially Over: Pentagon Reacts to Prigozhin Death,” Forbes Breaking News via YouTube, August 31, 2023; Marcel Plichta, Christopher Faulkner, and Raphael Parens, “Wagner’s Head is Dead, Now Bury the Body,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, September 6, 2023.

[88] “Building an Effective and Resilient Response to the Evolving Terrorist Threat in West Africa,” United Nations – UN Web TV, June 21, 2023.

[89] Anna Sylvestre-Treiner, “Niger: ‘Coup leaders who stir up anti-French sentiment in the Sahel distract from France’s real mistakes,’” Le Monde, August 4, 2023.

[90] “UK withdraws peacekeeping troops from Mali over Russian mercenary Wagner Group links,” ITV, November 14, 2022.

[91] “EU Planning New Africa Mission in Gulf of Guinea – Report,” Deutsche Welle, August 27, 2023.

[92] Parens, “Wagner Mutiny Ex Post Facto.”

[93] Kimberly Marten, “Why the Wagner Group Cannot Be Easily Absorbed by the Russian Military—and What That Means for the West,” Russia Matters, September 1, 2023.

[94] Ibid.

[95] Philip Wasielewski, “Expert Commentary: Prigozhin’s Death and the Future of Putin’s Rule,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, August 29, 2023.

[96] Dmitri Alperovitch, Jack Margolin, and Rob Lee, “What the Death of Prigozhin Means for Wagner, Russia and Ukraine,” Geopolitics Decanted Podcast, August 24, 2023.

[97] Ivana Kottasová and Stephanie Busari, “Can Wagner Survive, Even if Prigozhin Didn’t?” CNN, August 26, 2023.

[98] Raphael Parens, “The Wagner Group’s Playbook is here to Stay,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, March 18, 2022; Sean McFate, “Prigozhin’s Real Legacy: The Mercenary Blueprint,” New York Times, September 3, 2023.

[99] Author’s (Faulkner) interview, Wassim Nasr, September 2023.

Skip to content

Skip to content